Singing and Dancing Wherever She Goes

Simona's book about Maud Karpeles was published posthumously in 2011 and until I was invited to the its launch event, I had neither heard of Maud, or known that Simona had been working on her biography. Unlike many of her other books, therefore, I started this one in complete ignorance of her subject but decided as early as the preface that I would like her, mainly due to the description of her as 'small, distinctly plump...and witch-like in appearance'.

Maud was born in 1885, one of five children to London tea merchant Joseph and and his wife Emily. In her early adulthood she volunteered for the Mansfield House Settlement in Canning Town, working with children with disabilities and their families and where, with her sister Helen, she ran the Guild of Play. These weekly meetings were where local children went to sing and dance, and were Maud's first real involvement with dance. As she said in her unpublished autobiography, 'The quality of the material was probably somewhat mediocre, but it was the best I knew at that time; the children enjoyed themselves and so did I'. Her first real discovery of folk song and dance came in 1909, as Maud and Helen went to see a competition being held in Stratford upon Avon during their visit to a Shakespeare festival. The sisters started taking folk dance lessons on their return to London with the aim of teaching the Canning Town children, and subsequently formed their own folk dance group, which gave demonstrations to illustrate Cecil Sharp's lectures. And the rest is history, as they say.

But if, like me, you don't know what that history is, I'll give you a potted version. Maud and her folk dance group became some of the founder members of the English Folk Dance Society (EFDS) in 1911. She took on the role of amanuensis to Cecil Sharp on his numerous travels to the USA between 1915 and 1918 collecting and recording folk song and, following his death in 1024, undertook further visits both to continue collecting in the Appalachians and also in Newfoundland, a trip that Maud had starting planning with Cecil. The EFDS merged with the Folk Song Society in 1932 to form the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), which still exists today (and is, in fact, the publisher of this book) and Maud continued in a leading role on the executive committee for many years. She was instrumental in fundraising to build Cecil Sharp House, and in organising international folk dance and song conferences. These enabled her to continue her travels in Europe, Africa and the Caribbean throughout her life and into her 80s.

From what I've read about Maud, she was clearly ahead of her time in terms of her independence and individuality. A single young woman travelling through rural America with an older married man - they were away for nearly two years on one of their trips - would not have been easy in the early twentieth century and undoubtedly there were rumours about the nature of their relationship. These can't have been much quelled when on their return Maud moved into the Sharp family home, and continued to live there after both Cecil and his wife had died. Her passion for folk song and dance was immense and she never let the fact that she was a woman restrict her work or diminish her ambition. It seems to me that Maud's views on folk song diverged from those of Sharp in later years through her embracing of the international folk community, whereas today Sharp is often portrayed as somebody who collected only those songs that fitted his idealistic vision of folk song in its rural English idyll.

I really came to like Maud through reading this book, although I think it could benefit from being about 50 pages shorter; I must admit to becoming slightly bored of the frequent descriptions of the difficult travelling conditions or meagre accommodation that Cecil and Maud were forced to stay in during their Appalachian collecting trips. And I could have lived without so much detail on the various international conferences; an appendix might have been a better way to incorporate the level of detail but avoided the slight repetitiveness that I felt crept into the final few chapters.

This book, like In the Absence of the Emperor, tells you the story - what happened and when - and avoids any real analysis and, whilst full of quotations, these are almost all from two sources: Maud's unpublished autobiography and Cecil Sharp's diaries. Maybe there isn't much other source material, and the preface makes it clear that this book was an attempt to transform the autobiography into a publishable form, so maybe it was a conscious decision in order to retain a more autobiographical voice. An academic reviewer may feel this is to its detriment, but I didn't feel it made it any less of a interesting read as a result, especially given my previous lack of knowledge on the subject matter.

Simona lived for some years in Camden Town, with her sitting room overlooking Cecil Sharp House, so it has been good to find out about its history and the man who gave it its name, and that his collection might have been less rich and well documented had it not been for the contribution of a small, witch-like woman.

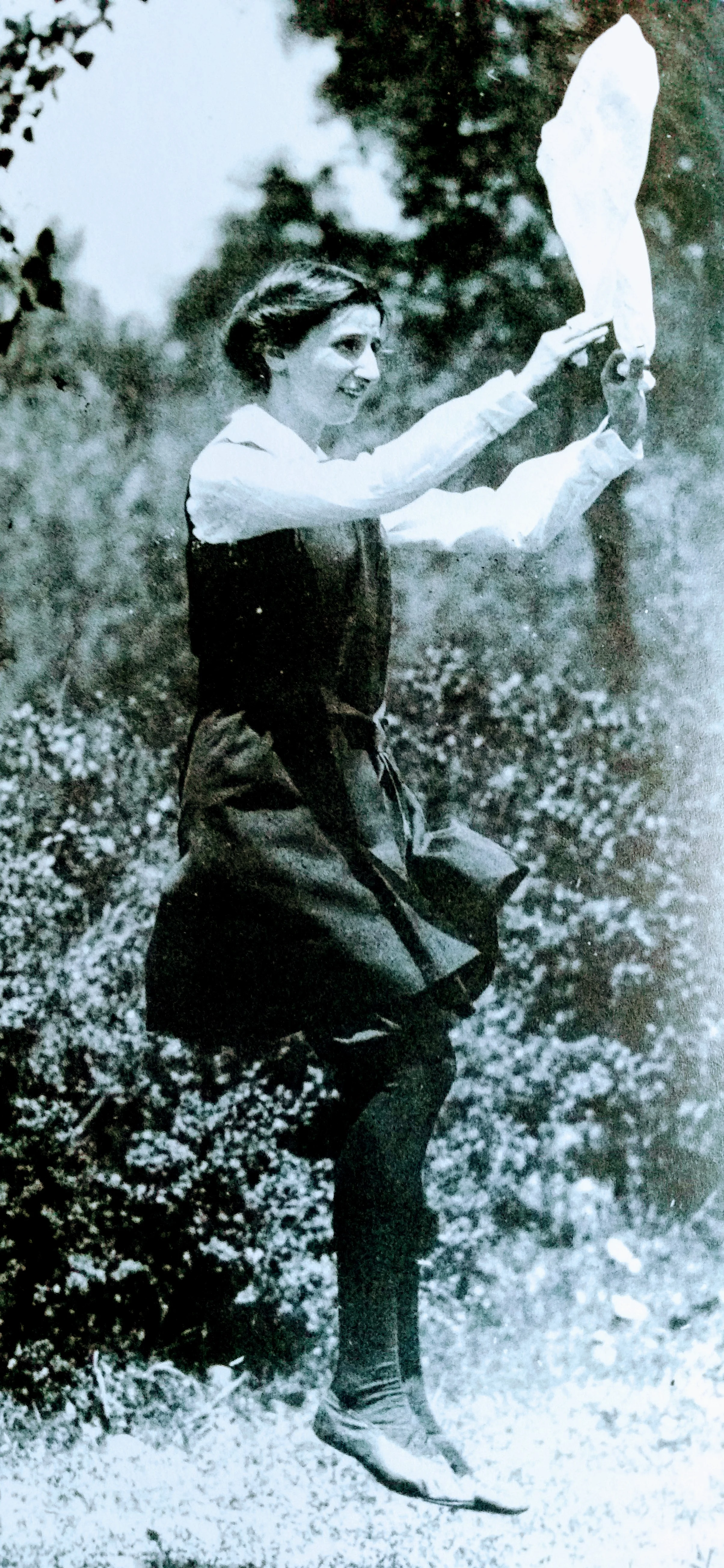

Films from 1912 showing Maud and Helen Karpeles, Cecil Sharp and George Butterworth.